Marcelo Mindlin speaks without haste. He takes long pauses before answering, as if mentally ordering each stage, and looks directly at his interviewer, journalist Luciana Geuna, as he recalls key decisions. He sits comfortably, leaning slightly forward, attentive to the exchange. There are no grand gestures or dramatic emphasis. His account unfolds calmly, almost didactically, with sentences linked more by reasoning than rhetoric, though at times they brush up against emotion. He occasionally smiles when recalling a work anecdote or the adrenaline of earlier years, but quickly returns to a reflective tone, more interested in explaining processes than in building an epic narrative.

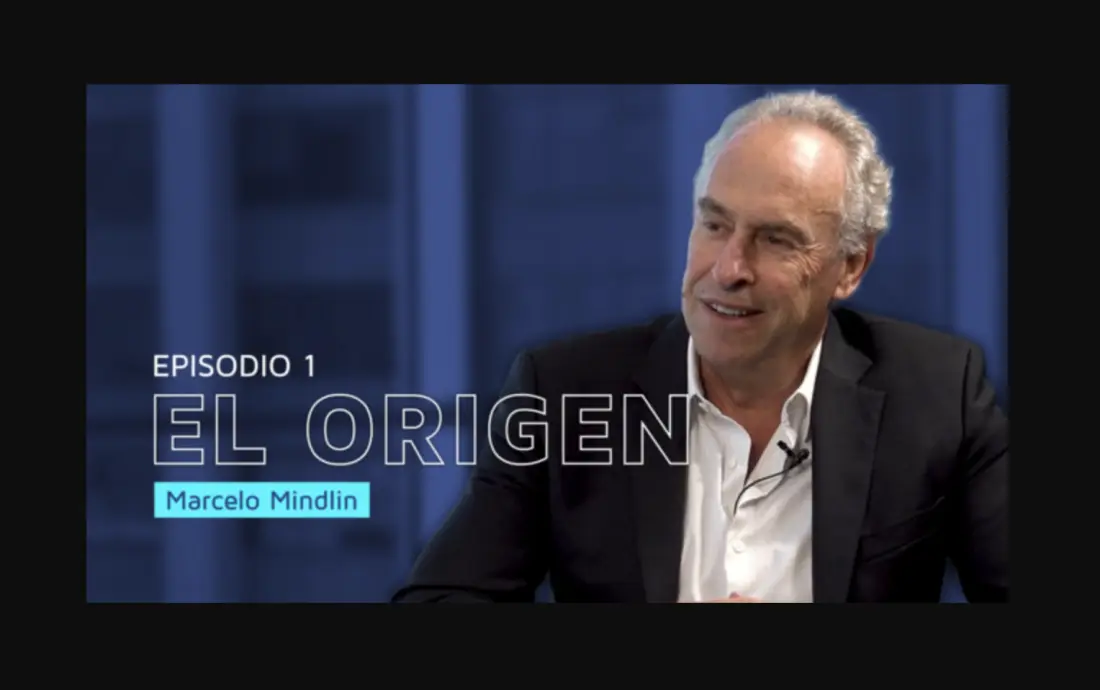

The conversation unfolds alongside the release this week of the first episode, titled “The Origin,” which is part of a special podcast series produced by Pampa Energía to mark the company’s 20th anniversary. The episodes, to be published on Spotify, also feature other partners, including his son Nicolás, business executives and representatives from the company’s foundation.

Across the series, the founding partners and senior executives revisit different chapters of the company’s history. In this opening episode, founder Marcelo Mindlin looks back at his personal origins and the decisions that shaped the creation of Pampa Energía, one of Argentina’s leading power and energy companies.

At the outset, Mindlin recalls that as a child he wanted to be a journalist. That early vocation stemmed from his family environment, particularly his uncle Jacobo Timerman, a central figure in Argentine journalism, whom he often saw at family gatherings. “Watching him, I wanted to be a journalist,” he says. Two experiences eventually pulled him away from that idea. One was advice from his father, whom he describes as “a very wise person,” who suggested he study economics as a solid foundation for understanding reality and practicing journalism. The other was a visit to the newsroom of La Razón newspaper, where Timerman bluntly warned him that “none of the projects here make money,” making clear that journalism was not an economically viable path. That was compounded by witnessing the aggressive treatment of a reporter in the newsroom. “That also definitively pulled me away from that initial dream of being a journalist,” he recalls.

That early interest in journalism took shape during his years at the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires, amid Argentina’s military dictatorship. Mindlin entered the school in 1977 and graduated in 1982, a period he describes as marked by “a lot of repression.” Along with a group of friends, he participated in a small clandestine magazine and experienced what he calls the adolescent political fervor and the feeling that it was necessary to fight the regime. “That’s what planted the journalism bug in me,” he says. At home, he grew up in a middle-class family, without luxuries, but with parents — both physicians — who strongly prioritized education. “Everything was very tight, but they gave us a very good education,” he says, explaining why they insisted he pursue a university degree.

While studying economics, Mindlin took his first job to gain independence and live on his own. He worked as an assistant to a family friend who managed wealth and invested in financial markets. “It was a job so I could live alone while I was studying,” he explains. Through that experience, he began to discover the financial world and the Buenos Aires Stock Exchange, an environment in which he felt at ease.

“They told me I had an extraordinary ability for mental calculations,” he says, noting that was when he realized he enjoyed that world and found it natural.

His first formal job came when he reconnected with Eduardo Elsztain at the stock exchange. They already knew each other: Elsztain had been a classmate of Mindlin’s sister and someone he had seen at social gatherings during his teenage years. Years later, they crossed paths again, and Elsztain invited him to join what was then a fledgling venture.

“It was Eduardo, me and an assistant,” Mindlin recalls. It was the era of President Raúl Alfonsín, marked by crisis and devaluation, and his first salary was $1,000 a month — a significant sum at the time. From there, he says, he began “navigating the waters of the business world.”

The two mentors, the dreams and the core project

From that period, he highlights two core lessons. One was Elsztain’s ability to think and dream big. The other came from Saúl Zang, who handled legal matters and taught him how contracts are negotiated and drafted.

“They were my two mentors,” he says. One taught him to imagine large-scale projects; the other how to translate those ideas into concrete negotiations, “starting from an extreme position and without embarrassment.” At 25, he had what he now describes as limitless capacity for work: extremely long days, whirlwind trips abroad, weeks without rest and an atmosphere filled with adrenaline but also enjoyment. “We worked a lot, but we had fun,” he says.

The partnership with Elsztain lasted 14 years. For much of that time, Mindlin says, the work was enjoyable and the team was very close-knit. Over time, however, differences began to emerge. “Decisions that used to be made by consensus stopped being that way,” he recalls. When he realized he was no longer enjoying himself or feeling fulfilled, he decided to strike out on his own. The decision was not easy. Being the No. 2 executive at IRSA at age 40 was, in his words, “a very comfortable position, with a lot of power and a lot of compensation.” When he told his wife, Mariana, she initially thought he was going to propose a separation. “When I told her I wanted to leave IRSA, she said, ‘That’s fine,’” he recalls, highlighting her support as crucial.

The turning point was understanding that he wanted to be the No. 1 in his own project, even if it was smaller, rather than the No. 2 in a large company. With that conviction, he called on key people around him: his brother Damián and Gustavo Mariani, then IRSA’s chief financial officer. “I invited them to join me in building a company,” he says. There was no clear plan. His initial idea was to take a sabbatical year after so many years of intense work. Before he even moved out of IRSA’s offices, however, the first opportunity emerged: the acquisition of Transener, Argentina’s main power transmission company, in the years following the 2001 economic crisis.

Energy, crisis and a strategy

Mindlin explains that energy was not part of his original plan. His background was in real estate, finance and agribusiness. But the crisis opened unique opportunities.

“Companies’ debt was worth very little,” he recalls, explaining that the strategy was to buy discounted debt and convert it into equity. That is how they began to learn the energy business — first with Transener, then with power generation, later with assets from Electricité de France, and years later with a stake in gas transporter TGS after the Enron crisis.

Pampa’s formal birth came when they acquired a small company that had been listed on the stock exchange since 1950 — an inactive meatpacking plant — and used it as a vehicle to consolidate all their energy assets. “That’s when Pampa Energía was born,” he says. They chose the name because “it had an Argentine connotation” and because, for foreign investors, “Pampa Energía clearly said where we were from and what we did.”

Consolidation followed with access to capital markets. Mindlin recalls that the first capital increase was around $100 million, used to finance the acquisition of Transener and other initial assets. Later, amid intermittent investor enthusiasm for Argentina, the group decided to tap international markets with a share offering. The roadshow included Europe and the United States and culminated in a placement of between $400 million and $450 million. “That’s when we started with enough capital to continue this whole process,” he says.

That moment marked, for him, the consolidation of Pampa as his own project. “The day I left IRSA, I felt free,” he says. Beyond growth in size or assets, he emphasizes the importance of leading a project alongside a chosen team. “I didn’t care how much you grew, but about being in your project, with the team you want to be with, trusting your work and the team’s work,” he says. He also highlights a key difference between Pampa and other companies in the sector: “The founding partners all work every day,” watching numbers and costs “as if it were our own money.”

Trust in the team and opportunities

Looking back, Mindlin returns to an idea that runs through Pampa’s entire history: trust in the team and in the country, even in the toughest moments.

“I always trusted my team, and I always trusted that in Argentina crises are harsh, but they also give you unique opportunities to grow.”

That mindset was critical in the years after the 2001 crisis, when many companies were in default and assets traded at deeply depressed values. For Pampa, that adverse environment also became the ground on which its growth was built.

Twenty years after its creation, Pampa Energía stands as the result of a series of decisions made amid high uncertainty, where reading the economic cycle, accessing capital and executing effectively mattered as much as the underlying resource. The company was born in a country in crisis, grew in a fragmented market and ultimately consolidated in the energy sector, which has once again taken center stage in the global debate.

The current context reinforces that reading. The energy transition is advancing more slowly than expected, electricity demand is growing rapidly, and supply security has returned as a priority. In that scenario, natural gas has emerged as a structural component of the global energy system, and Argentina’s Vaca Muerta shale formation is positioning itself as one of the few resources capable of meeting that demand at scale and competitively. For companies like Pampa, the challenge is no longer proving the resource’s viability, but turning it into bankable, exportable and sustainable projects over time.

The company was born in a country in crisis, grew in a fragmented market, and ultimately consolidated itself in a sector — energy — that is once again taking center stage in the global debate.

Mindlin’s story leaves an additional takeaway: energy is not built on assets alone, but on teams, patient capital and long-term decisions. In an increasingly fragmented global market, where LNG has become both a geopolitical and commercial tool, developing Argentina’s gas and energy sector requires more than cyclical opportunities. It requires continuity, clear rules and execution capacity. In that sense, Pampa’s trajectory functions less as an origin story and more as a roadmap for how to build an energy company in Argentina.