The capture of Nicolás Maduro on Jan. 3 by U.S. forces and the questions surrounding Venezuela’s political transition have rattled global energy markets.

While there is broad agreement that the South American country holds the world’s largest proven crude reserves — about 303 billion barrels — leading international analysts share a common assessment: the short-term impact will be limited, any recovery will take years, and outcomes will hinge more on institutional, legal and geopolitical factors than on a simple lifting of sanctions.

Javier Blas (Bloomberg)

Javier Blas, Bloomberg’s chief energy columnist and co-author of “The World for Sale,” focused his analysis on the geopolitical control the United States is exerting over Venezuelan crude. In a video column published Jan. 8, Blas described the situation as the emergence of a U.S. "oil empire” stretching from Alaska to Patagonia, with Washington acting as the de facto intermediary for PDVSA’s oil sales.

Blas notes that the U.S. Department of Energy has begun directly marketing part of Venezuela’s crude output and that the Trump administration is seeking to use the proceeds to compel purchases of U.S. goods. In his view, this control reduces the risk that oil revenues would finance hostile regimes — as previously occurred with China and Iran — but also caps the speed of any rebound. Private companies, he argues, will only enter if Washington guarantees legal certainty. Blas forecasts WTI prices stabilizing below $60 per barrel in the medium term if Venezuela adds 300,000 to 500,000 barrels per day of supply in 2026.

Francisco Monaldi (Baker Institute, Rice University)

Venezuelan economist Francisco Monaldi, director of the Latin America Energy Program at the Baker Institute, is widely regarded as one of the most knowledgeable analysts of Venezuela’s oil sector. In recent days, he published a Substack article titled “Fixing the Venezuelan oil industry will take time, money, and — most importantly — institutional change,” and appeared on podcasts while commenting in the Financial Times and The Wall Street Journal.

Monaldi estimates that merely returning to 2.5 million to 3 million barrels per day — levels seen a decade ago — would require more than $100 billion in foreign investment over the next decade. He highlights three critical barriers:

- the destruction of PDVSA’s institutional capacity

- the need to resolve outstanding legal disputes, including more than $10 billion claimed by ConocoPhillips

- the creation of an attractive and stable contractual framework

While Chevron is best positioned to benefit quickly — producing about 150,000 to 200,000 bpd under a special license — Monaldi warns there will be no “quick wins” without deep reforms. He sees opportunities for U.S. Gulf Coast refiners, which are well suited to Venezuelan heavy crude, but stresses that flows to China would decline gradually, not abruptly.

Artem Abramov (Rystad Energy)

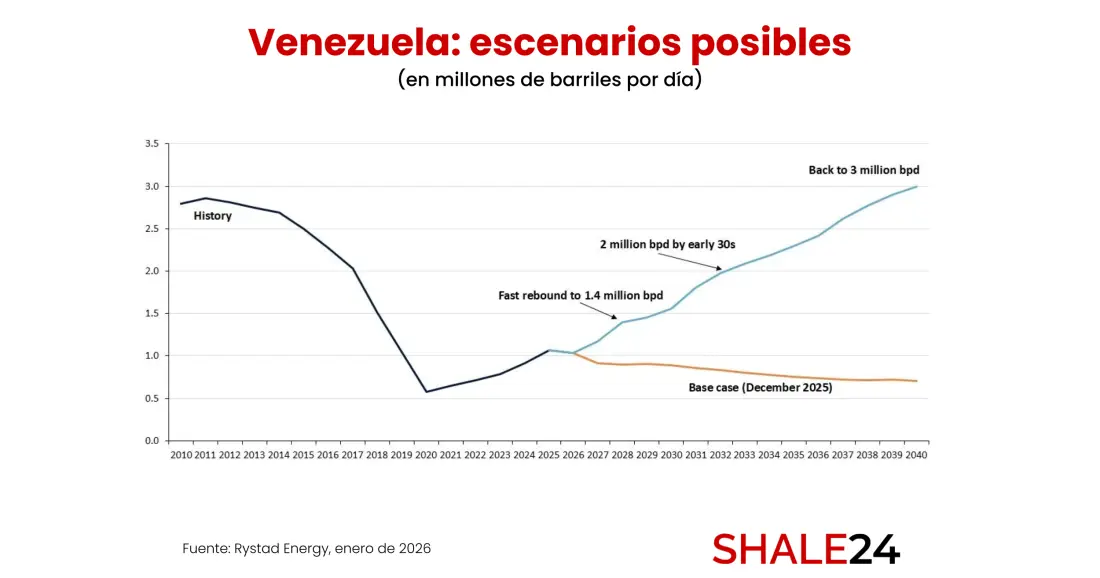

Artem Abramov, senior partner and head of oil and gas research at Rystad Energy, published a study analyzing the market impact of Venezuela’s situation.

“It is technically possible to revive Venezuelan oil production, but we are talking about a 15-year horizon for crude supply to return to 3 million bpd if the new investment cycle starts now,” Abramov said.

“We are talking about stable investment run-rate north of $10 billion/year until 2040 to bring production to 2 million bpd by early 30s and 3 million bpd by 2040. A large portion of this investment is needed just to repair existing pipelines, upgraders and port infrastructure at the start of the cycle. More than $30 billion of external capital has to be injected at the start of the cycle to develop the initial momentum.”

He concluded: “oil prices above $70-80 might be needed in the 2030s to get all the way to 3 million bpd. With lower prices, 2.0-2.5. million bpd is more realistic ceiling. Bottom line: recovery is possible but requires patience, massive capital and sustained high prices – not an easy win."

Other perspectives

- Daniel Yergin, vice chairman of S&P Global and author of landmark works such as “The Prize” and “The New Map,” offered a long-term, historical perspective. In recent comments, Yergin emphasized that much depends on politics and who is actually in charge. He acknowledged the vast potential of Venezuela’s reserves but noted that production has fallen more than 75% from its 1990s peak due to underinvestment, sanctions and mismanagement. Comparing Venezuela with other post-sanctions cases such as Iran and Libya, Yergin concluded that recovery will be far slower than many expect because of collapsed infrastructure, the exodus of technical talent and the need to renegotiate contracts. He does not expect a meaningful impact on global prices before 2028-2030 and warned that any increase in Venezuelan output would likely be absorbed by still-growing global demand, particularly in Asia.

- John Kemp, senior market analyst at Reuters, took a more quantitative and less geopolitical approach. In recent writings, Kemp noted that U.S. Gulf Coast refineries are the natural buyers of Venezuelan heavy crude and that a significant return of those barrels could marginally pressure refining margins and diesel prices. Kemp observed that hedge funds adopted bearish positions in oil following the announcement of Venezuela’s political transition, reflecting expectations of higher future supply. However, he agrees with the broader consensus that the global impact will be minimal: Venezuela accounts for less than 1% of current global production, and its recovery will not alter the existing OPEC+ and U.S. shale balance.

- Helima Croft, global head of commodity strategy at RBC and a former CIA analyst, is among the most respected voices on the intersection of oil and geopolitics. Her view is notably cautious. While she acknowledges that full sanctions relief and an orderly transition could add several hundred thousand barrels per day within 12 months, she stresses that Venezuela’s infrastructure is so degraded that it would require annual investments of about $10 billion just to bring it back to baseline condition. Croft highlights the lack of immediate enthusiasm from major oil companies. The majors are not eager to take political risk in a country with decades of expropriations and corruption. Her conclusion: Venezuela will not be a game changer in 2026 or likely in 2027; the global market will continue to be dominated by OPEC+, U.S. shale and Asian demand.

- John Arnold, the legendary energy trader and philanthropist, struck an even more skeptical tone. In posts on Jan. 7, he noted that Chevron shares were trading below pre-capture levels, reflecting market doubts about large-scale investment by major oil companies. Arnold questioned whether majors would risk tens of billions of dollars without solid guarantees of stability and returns. As a positive side effect, he pointed to a reduced risk discount on Guyana’s reserves — which are disputed with Venezuela — benefiting ExxonMobil and other operators in the Stabroek block.

In conclusion, experts broadly agree that Venezuela will not trigger an immediate supply shock or a dramatic price collapse. The most likely impact in 2026 is a modest increase of 200,000 to 500,000 bpd, strategic benefits for U.S. refiners and a gradual diversion of flows away from China and Russia. The true upside — returning to top-five global producer status — depends on deep institutional reforms, massive investment and a stable political transition. For now, the global oil market remains far more focused on Riyadh, Texas and Beijing than on Caracas.