Last Tuesday, Trafigura, one of the world’s largest commodity traders, released its 2025 results and outlook for 2026.

Saad Rahim, the company’s chief economist, warned: “Oil markets were expected to see large surpluses, but they did not materialise, at least not in the key pricing centres. Global oil demand was weak, as most participants had forecast. Total global demand growth in 2025 was just under 800,000 barrels per day, a marked decline from the pre-pandemic annual average of just under two million.”

According to Rahim, gasoline no longer drives growth in global oil demand. Instead, demand growth now comes primarily from the petrochemical industry and jet fuel. Still, global oil demand showed some strength this year, particularly in the distillates sector.

Refinery disruptions, especially unplanned outages, and the slow ramp-up at Nigeria’s Dangote refinery kept distillate inventories in the Atlantic Basin low throughout the year. This situation was worsened by repeated attacks on Russian oil infrastructure, which reduced product exports. The shortage kept refinery margins strong for most of 2025, limiting crude prices.

The risk of supply shortages due to Russian sanctions benefited crude producers, along with the brief but dramatic conflict between Israel and Iran early in the year. These factors kept crude prices between $65 and $70 per barrel for most of the year and created strong backwardation, with buyers paying more for immediate delivery than for future barrels.

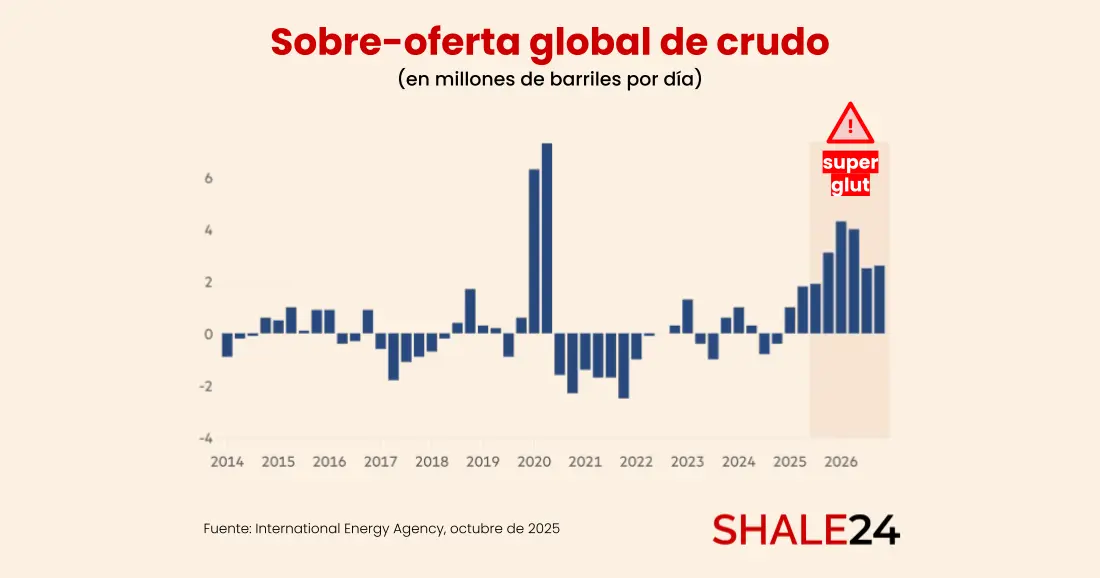

What the super glut is and why it is expected in 2026

The term “super glut” has emerged in oil market discussions as a way to describe a scenario of massive oversupply that could flood the world with crude at extremely low prices. It is not a sensationalist invention, but a technical forecast based on production, demand and global market dynamics.

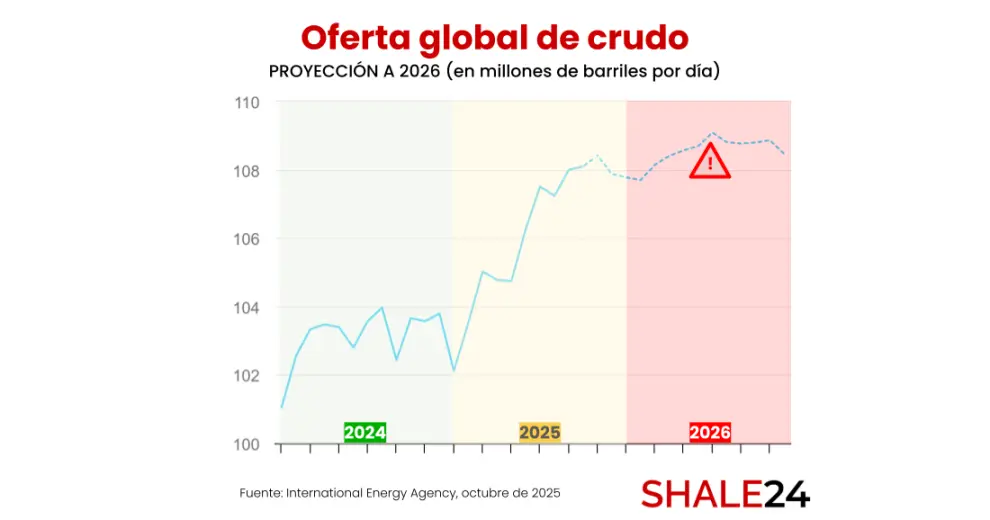

Rahim added: “In 2026, supply growth is expected to significantly exceed demand growth. Forecasters are virtually unanimous in projecting record oversupply that could surpass pandemic levels. Supply is expected to grow by approximately two million barrels per day.”

This growth will be driven largely by long-lead projects in Latin America — led by Guyana and Brazil — and North America (Canada and the U.S. Gulf Coast), whose investment decisions were approved years, and in some cases decades, ago. As a result, these projects are unlikely to see production cuts, even in a lower-price environment.

"The same may not hold true for other producers, especially if inventories start to build early in the year and prices react accordingly. Producers in both the US and OPEC+ may view the situation as untenable and dial back production, which might then lend some support to prices," he said. “The largest wild card in oil markets remains China's strategic buying – if this continues or increases, it will go some way towards addressing the supply overhang, although it is unlikely to resolve it. Conversely, a slowdown would exacerbate the situation.”

How Vaca Muerta could adapt to this new scenario

The global oversupply scenario in 2026, with Brent crude projected below $60 and possibly near $50 per barrel, will force Vaca Muerta operators to adjust their strategies. Although the basin is still considered globally competitive, prices in this range could test the profitability of some specific projects. Adaptation scenarios would focus on efficiency, selective investment, and infrastructure.

Operators may choose to concentrate capital investment and drilling only in the most productive areas. In this case, the goal would be to maximize return on investment and per-well productivity, since these zones have an estimated break-even of $45 to $50 per barrel, remaining profitable even at $50 per barrel. Technically, operators would likely continue drilling longer lateral wells and increasing the number of fracture stages per well, allowing more oil extraction at better long-term unit costs.

Despite these measures, price uncertainty will likely lead to much more cautious investments. Projects in less proven areas or with higher operational costs (such as some zones in Río Negro or newer blocks) could see delays in startup or even be put on hold. It is well known that shale oil development profitability is far more sensitive to price drops than conventional crude.

When oil prices fall, operators are often forced to focus more on natural gas, especially if they produce associated gas, since shutting in all production is not feasible. Selling gas at low prices helps keep oil wells operational, as is already observed in Vaca Muerta.

In any case, a low-price environment often acts as a catalyst for market consolidation. The largest and most efficient players (such as YPF and Vista) are likely to acquire or partner with smaller companies that cannot sustain high operating costs and lower profitability. The recent exit of some major international oil companies could continue if the global price environment discourages parent companies from investing additional capital in a volatile market, leaving more room for local operators.